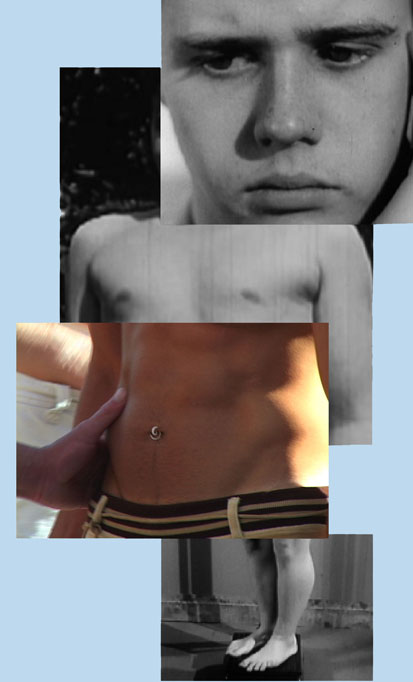

Do I Look Fat? A Documentary on gay men, body image, and eating disorders.

In 2005 the feature-length documentary, Do I Look Fat?? was released. This site was created to promote the film as well as provide links and resources and information about hosting the film.

The content below is from the site's 2005 archived pages.

This site's message is as relevant today as it was when the film was first released.

And I should know. My boyfriend who is a successful interior designer struggles with this issue. He spends hours pouring over contemporary Italian dining tables at his favorite Philadelphia furniture store's website, discusses the pros and cons of each fabulous table mentioning both the Italian manufacturer and designer of the table, wows the clients with his exquisite tastes in design, and then at the end of the day as we sit down to celebrate the success of the current job at a marvelous restaurant, he will just pick at a salad, sip some wine, and bemoan how fat he is. Really! He looks great, we have an amazing apartment which, of course, he totally decorated with modern Italian furniture and lighting, we go on vacations to exotic get-a-ways - he's a success. But....And that's the conundrum he faces everyday. And it's so devastating.

No one realizes what he goes through. To his clients he is a genius. Just this past week he received a phone call from a client who was having a total melt down because one of her Bengal cats had knocked over bottle of fine french wine (red no less) onto an oriental rug. What was she to do.The rug was ruined. "Not so,"" said my boyfriend. "I know the perfect NYC carpet cleaner company that does wonders with such stains. They specialize in the cleaning and repairing of oriental carpets. Your Tabriz antique Persian rug will be in good hands. Do not fret. I shall call them and take care of everything." And he did. The client was thrilled with the results. I just wish someone could help my boyfriend as swiftly and successfully as he helps his clients.

My boy friend also helped my mother decorate her room at a Bel Air assisted living community in Maryland near my bother when she decided (bless her soul) that she no longer felt comfortable living on her own, yet didn't want to burden any of her children. My brother really wanted her to live with him, but she was adamant. Moving into Hart Heritage Estates in Forest Hill was perfect for her. Situated on 6.5 acres of park-like grounds, all the residents, including my mother, have a front row view of nature through all the seasons. As spring rolls around again, I can imagine her looking out the large window of her wonderfully furnished room (thanks to my boyfriend's immaculate tastes) with her binoculars and a pad of paper so she can jot down each type of bird she sees. My Mum is great with my boyfriend. She seems to understand him better than some of the doctors he has been to. During this past year with the pandemic making visits to my Mum impossible, she and he have spent a lot of time Facetiming. I feel fortunate to have a Mum who is so sympathetic to my boyfriend's fat-phobia. I know she has even watched Do I Look Fat? several times.

About the Film

Do I Look Fat? is a feature-length documentary with fat on the brain -fat that we feel, fat that we think and all sorts of fat problems that manifest from fat-phobic

thinking inside the fat-wary gay community. As one person puts it, "fat is the little word with big meaning."

So why are we so scared of fat? And how has body obsession become such an identifying force within the gay male community? Through the personal stories of

seven diverse men, all with eating disorders, who identify as gay, and one as bisexual, the complexity of this "self-esteem disorder" becomes apparent.

Their experience is supported by several experts in the field of eating disorders -an M.D. of a renowned eating disorder clinic, an art therapist, and a gay therapist who's battled with his own eating disorder- in an effort to make sense of some of the trigger issues at the heart of much eating disordered behavior; issues such as childhood wounding, internalized homophobia, and substance abuse. These and other systemic reasons for eating disorders are explored with a candid sensitivity, and at times, a refreshing levity.

About the Filmmaker

Travis Mathews holds a Masters in Counseling Psychology from the California Institute of Integral Studies in San Francisco, CA. With his complimentary interests in psychology and film he plans to continue working on projects that reflect this intersection of ideas. Do I Look Fat? is his first feature movie.

Travis, along with Brad Kennington, M.A., LPC, LMFT, is in the preliminary stages of developing an eating disorders IOP that would uniquely focus on men. It will be the only such IOP in central Texas and one of few in the country.

Travis currently lives in Austin, TX with his partner, Keith Wilson and their dog Rufus.

Getting Over It

I began working on Do I Look Fat? in the summer of 2003 not long after superficially coming out about my own eating disorder. I say superficially because I really only came out in name. I continued to think like someone with an eating disorder, preoccupied with silent questions like, am I allowed to eat now, and later, how much am I allowed to have? I’m beginning to acknowledge that these thoughts might always be there, the difference is in how I accept them as part of who I am.

I read somewhere that on average it takes people around seven years to get over their eating disorder. That’s quite a statement for someone just coming out. There’s the number of years component –seven, which sounds inconceivably out of reach; then there’s the getting over it piece –which I can only now look at with something of a critical eye. I won’t pretend to speak for all people suffering with some variant of an eating disorder, but for me, it’s much less about getting over it and more about accepting myself.

So you might imagine how there was a lot wrapped up in my decision to make this documentary, not least of which was my unconscious hope that it proved to myself, and others, that I was over it. I followed that if I could make a movie about eating disorders and discuss them with the detached air of an expert, maybe I could believe my self-healing convictions. Seven years? -pshaw, I’d do it in one. I was ready for something new, and the movie was one way of initially distancing me from the personal work I needed to face.

In the planning stages I got lost in all the possibilities of constructing such a multi-faceted issue. It saw it as an issue, and that’s how I’ve mostly approached the documentary. But as I began to visit with each of the men you see in the film, the detachment started to wane. I learned from their no-holds-barred candor that it takes a tremendous amount of strength to be this vulnerable and share what hadn’t been modelled before them. I find this especially valuable because men (gay and straight) have been virtually absent from the eating disorder landscape, where resources are difficult to come by and exposure anectdotal. It certainly characterizes my coming out experience. I figured that if I just kept quiet long enough it might go away on its own. I would outstare it, outsmart it; maybe no one had to ever know.

The lack of exposure I’m speaking to was another driving force behind my decision to make this movie. Disclosure is hard and needs to be handled with sensitivity, but it needs to be handled eventually. It seemed suspect to me that the gay community, one with a history of confronting difficult issues with an outspoken tenacity, would turn a blind eye to body image issues and eating disordered behavior. At the heart of this, I learned, were a slew of issues that often stemmed from the same ones that made standing up as a big homo such an ordeal. Again and again, I heard men talking about femininity and masculinity, personal battles with childhood wounding, and a desperate attempt to control something in the face of insecurity. It felt right because I felt it myself and I understood the pull to look the other way. It’s a self-esteem disorder, as Rafael says in the movie, and one that affects individuals as well as communities.

My hope is that these stories will help in normalizing eating disorders for men, for gay men, in some measure, and to make that someone watching realize that he’s clearly not alone. It’s a process, it’s a difficult process that won’t go away in isolation. It has to start somewhere.

Ted Weltzin, M.D.

In January 2004, dir. Travis Mathews went to Rogers Memorial Hospital to interview Ted Weltzin, M.D., Medical Director of the Eating Disorders Center, a residential facility for treating eating disorders in men and women. The following is a partial transcript from that interview.

I’m a new patient at Rogers, give a brief overview of what I should expect.

At Rogers we have a commitment to treating males with eating disorders. We’ve had a lot of experience working with males and have done research looking at the causes, what are the components that go into making treatment successful. Part of that commitment is that we treat males as a separate group so that males are in treatment with other males; we recognize that treatment is really most effective when it occurs with other males who have eating disorders. One of the biggest things people report to us coming into treatment is that they felt very isolated with their illness. Often, people will be in treatment centers where most of the patients are female. There may be one other male, often times no other males in a treatment setting and the males report a lot of shame associated with having their illness, feeling like people don’t really understand what’s going on with their eating disorder.

And what about Rogers being the only male residential center in the country?

Well, we are the only residential program in the country that has a separate program for males and the reason for that comes down to commitment. Incidence of eating disorders in males is about 1/10 of what it is with females. It’s rare in a sense, but more common than most people realize. If we look at the population in general, there are a lot of males out there with eating disorders,. However, relative to females, the rate of males with eating disorders is much less.

Why is it so hard to capture an accurate picture of how prevalent this is among men?

The question of how prevalent this is among men is a difficult question. The main reason being that males typically don’t seek health treatment and they don’t seek treatment for this problem, so it’s impossible to get an accurate reflection of how prevalent male eating disorders are in the population. A great example of this is an opportunity I had last year to treat a male in his 40s. He had had clear cut bulimia for about 25 years but he was not aware that he had an eating disorder, even though he was binging and purging basically for 25 years. That’s just one example of asking someone if he has an eating disorder and he says no, but clearly he does. The shame involved in it, the feeling that this is a woman’s illness, what does this mean for me?, is simply a big obstacle and men simply won’t say that they have an eating disorder, they will just not disclose it, for fear of being made fun or of the admission dimensioning their masculinity.

And your typical health care providers don’t often don’t consider the possibility of eating disorders in males. We’ll see a man who is clearly starving and malnourished go into the doctor and the physician will not ask him about an eating disorder. A lot of things in society are really making it difficult to identify people, including finding treatment resources for men. You can’t go in the phonebook or go on-line and figure out where to get help -- it’s very difficult. The majority of eating disorder literature and resources are geared to females so that creates another obstacle in getting treatment.

We’re in a time that’s really in flux where eating disorders for males are increasing greater then eating disorders in females. I think that has to do with a blurring of roles that’s occurring in society over the past several decades, and it’s putting stress on both males and females in different ways. The roles aren’t clearly defined and as result we see a lot of behaviors or illnesses that have been associated with one gender or another that are changing. An interesting example of this is steroid abuse and women. The group that is having the greatest increase in steroid use, which we typically associate with men, is women. Conversely, with men, we’re seeing illnesses like anorexia and bulimia that I think some of the pressure with the increase in rates has to do with the changing of roles in society -- not to say that that’s a bad thing, but it’s influencing rates of these illnesses.

Probably the last factor that we frequently see here is the whole stigma: What does it mean if I have an eating disorder? When eating disorders in males was first talked about, there were a number of things that were first associated with it. One was the kind of athletic competition that puts males at risk for eating disorder, such as gymnastics or wrestling. And there’s the whole issue of homosexuality and eating disorders. Often times, if we have a young male who comes into the program, family members are kind of linking eating disorders and homosexuality together and often the first thing they’ll ask without any other evidence is, If he has an eating disorder, does that mean my son is gay? Often the patients will say that themselves, and it creates a situation, another level of complexity as to what it means to have an eating disorder and another obstacle to really seeking help for an eating disorder. Eating disorders tend to occur in teenage years where people are experimenting with and questioning their sexuality. This also adds to the level of confusion people may have, creating added stress and another barrier to getting treatment.

What about the gay men/adolescents you do see, what histories do they share?

One is the issue of self-esteem and how I think the stress of being gay, the stress of coming out, the stress of dealing with parents and peers in a high-school setting, there isn’t a lot of, in my experience, support in those settings for helping people figure out who they are and be accepted and there’s much more negative pressure on self-esteem than positive pressure struggling with that issue, and as a result they deal with that a number of different ways.

We’ll see people who have gotten into alcohol or drug problems, then transitioned into an eating disorder, it’s not uncommon for people to have gone through a period of alcohol and drug use, gotten sober and the eating disorder begins, that’s a typical thing. Often times, issues around not feeling like someone is living up to parental expectations, if someone’s not your typical jock or doesn’t want to do all the sports thing when they’re younger and maybe interested in other areas, you’ll frequently see a lot of issues with both parents, particularly with fathers and feeling that they’re disappointed which further adds to difficulties with self-esteem and often times people will deal with that distress through restricted eating through purging. Parents will typically comment about this connection between body shape, body fat and athletic activity. Frequently parents will say to someone, you need to be more active or why aren’t you participating in athletics, at a time when their body is changing, at a time when it’s kind of normal to have body fat, at a time when as people are maturing, their bodies aren’t going to be that well developed, that’s a time when people will get into restricted eating or binging and purging.

Binging and purging becomes a factor when people understand that it’s a way to deal with uncomfortable emotions, so that’s either restricting or binging and purging in a setting when people are questioning their self-esteem, not quite sure about who they are, feeling ashamed, feeling like there’s no one they can talk to, they tend to isolate and think, how can I deal with these feelings, and one of the ways is developing an eating disorder.

How do the gay men and straight men interact here?

I can’t recall any situations where people have had a problem with who’s in their group. It seems to be that there’s such cohesion with the men who are in group, irrespective of their sexual preference. I think it highlights the issue, which is people are dealing with the same thing, which is eating disorders have to do with body image, self esteem, how we deal with stress and how to be productive in our life, which how I look at it, it’s how to be productive in terms of interpersonal functioning in relationships, no matter who that other person might be.

How does childhood bullying and teasing play into things?

One of the most interesting things with males and eating disorders is the role that peer relationships, teasing, bullying, the impact, how that really seems to play a big role with males who develop eating disorders. It’s really surprising how many males will come in and talk about specific issues where they have been bullied, teased, repetitively. And that kind of initiates the eating disorder symptom. It’s a very destructive experience, a painful one that often people really don’t know how to deal with.

People will say, they’ll kind of push kids to be a part of the crowd if they’re complaining about how someone is treating them. Well, you should make friends with that person, or join a sports team. The message people get is, you need to be different to deal with that. They say, oh, it’s not that big of a deal. -of course it’s a big deal. They often say, just ignore those people. But ignoring people is kind of isolating. Or get involved in something else, play soccer, play football, do this. People may not want to do that. There really isn’t a good mechanism to help people from that type of behavior when they’re younger and as a result you’re stuck with these feelings you’re not sure how to deal with. Often times they’ll feel bad about themselves, it will negatively impact their self-esteem and one way they deal with that is by saying, okay, what can I change. Well, I can workout, I can get stronger, I can get thinner, and that gets them into the eating disorder behavior and it goes from there. I would say that over 50% of the men we see have had clear-cut traumatic experiences around bullying and teasing in youth.

There’s a saying that the best oppressors are the oppressed. How does this relate to gay men/adolescence who are oppressing their bodies with an eating disorder?

If we assume that eating disorder symptoms are really destructive to ourselves, to our bodies, in some ways punishing ourselves, it then becomes why would people kind of pay for a bad experience that’s happened to through carrying out further bad experiences against themselves. And I think that it has to do with almost a brainwashing that happens for some people who’ve been in traumatic situations. They feel they don’t deserve anything better, they don’t deserve to be happy, they don’t deserve to feel good about themselves. And they punish themselves. One of the ways they can punish themselves is through an eating disorder. If you talk to people with eating disorder, this is described very frequently. People will say, I’m a bad person.

One of the things we want to get to in recovery is to get people to a point where they say, do I deserve to recover? And obviously if people get to a point where they say, ‘you know, I deserve to feel good about my body, I deserve to feel that I’m a worthwhile person.’ If they’ve spent years and years and years, either their environment telling them they’re a bad person or taking that on, it’s a very difficult shift to make in giving that up. So the punishment does become a big part of this for some people. Often times kind of taking on a life of it’s own irrespective of the maybe why it started. Maybe it started, as we’ve talked about, with bullying and teasing, traumatic family experiences, often times issues of sexual abuse, issues of traumatic sexual experiences will also lay on a layer of guilt on people, and the way they deal with it is to continue to punish themselves for something that they had no control over yet feel guilty about.

Eating disorders that are rooted in childhood/adolescence versus ones that are adult on-set, are they more difficult to handle, approached differently?

The age of onset for eating disorders tends to be a little bit different in males than in females. Males with anorexia tend to develop it earlier than females, early in adolescence, but there are males who develop it later in life in their teenage and young adult years, where bulimia tends to come on later, in late teens and early 20s in males. The age of when the eating disorder starts is important in that it has to do with their level of psychological develop has been. What eating disorders do in our experience is it kind of puts their psychological development on hold. If you develop an eating disorder at age 15 and have been dealing with their life and emotions and stress through binging and purging or anorexia for 5 years, even though they may be 20 years old, they’re really psychologically functioning as a 15 year old. So, the age of onset does have a lot to do with it. If they develop it later, maybe they’ve had the chance to develop psychologically more skills in terms of dealing with that. Whereas if they develop it younger, not only do they need to recover from their eating disorder, but they have to do a lot of work maturing emotionally, maturing cognitively. So, that is really the biggest factor in terms of when the eating disorder begins. Just what is the quality of life and what are the coping skills and abilities to tolerate stress prior to their eating disorder beginning that they can access as a resource when they are in recovery or ultimately recover from their eating disorder.

In regards to gay men, can you go into the connection between the on-set of an eating disorder and the internal struggle of dealing with one’s sexuality.

You know, I think one of the issues relative to gay males is how an eating disorder really has effected how they deal with family members and co-workers around their sexuality. One of the aspects of recovery has to do with, kind of reassessing how they interact with their family and loved ones around their sexuality. Like anything else, there tends to be a fair amount of unresolved issues that just haven’t dealt with. People may have come out and superficially dealt with these issues, but in terms of dealing with them emotionally, a lot of times they have to rework that. That’s one of the issues that happens, often times you’ll see that with family members. So that’s one of the issues we frequently see with eating disorders, just being more open and talking about their sexuality is another issue people will superficially touch on that, but not kind of get to, but haven’t gotten to a point where they can figure out what role, how do they want to deal with that. They tend to get anxious and overwhelmed with it and then the eating disorder kind of blocks that.

I think that one of the aspects about the work we do with gay males is to kind of get them to really make, not necessarily make decisions, but reassess aspects of how they’ve dealt with their sexuality when they had an eating disorder and how are they going to deal with their sexuality if those are issues that need to be dealt with without an eating disorder.

Do you feel some gay men are suppressing their sexuality by making themselves uncomfortable or desexualized with food or controlling that, controlling libido?

I don’t think you typically see people using their eating disorder as a way of reducing sexual urges, sex drive. With anorexia you will see clear reductions in testosterone which is going to reduce sexual feeling, sex drive, but what I think it has to do with more is people using their eating disorder as a way of not resolving issues around function with other people. Whether it’s a partner, whether it’s issues in a relationship that need to change. Sometimes people with eating disorders and low self-esteem will feel very ineffective in dealing with relationships and they have a hard time getting their needs met because of self-esteem issues. So, if for that person, for example, if they’re in a relationship where they’re giving more than they’re getting emotionally, or decisions are being made that they don’t feel like they’re a part of, part of the process in recovery is to feel more like it’s a 50/50 type relationship where they can get their needs met, where they can get some control over how the relationship goes and these types of things.

So, I think that we don’t see a lot of it as a way of reducing sexuality as a kind of solution for feelings about sexuality but it does tend to kind of reduce the ability with how people deal with people, whether it’s a partner, whether it’s an issue around how one’s family is dealing his sexuality, and a great example is as someone dealing with family members and what their level of acceptance of someone’s sexuality is. If someone has an eating disorder what they may do is feel very uncomfortable or not like how people are dealing with them around their sexuality, but they never kind of deal with it effectively. So part of the recovery process when people are not in their eating disorder, figuring how to deal with these issues differently is they kind of have to address these issues again with family members, friends, siblings, with co-workers, and so my experience has been that it’s really more of the emotional aspects of sexuality that need to be addressed in recovery as opposed to say, physical sexual urges.

Talk about self-medication through consumption.

One of the things that happens with people with eating disorders, is that they will use food and other things as a way of trying to feel better, trying to feel better emotionally, trying to feel more in control. Often times, with males, you’ll see people use alcohol or drugs as a way of self-medicating themselves. And one of the interesting things that happens with people with eating disorders, is that people will recognize that their eating disorder symptoms will help modulate how they feel, give them the sense of more control, which often times is feeling less anxious, for example, people with anorexia, when they starve themselves, feel less anxious, they feel less stress, it gives them, physiologically a sense of control. And they become addicted to that, not addicted in the normal type of drug abuse sense, but they recognize that this works, that if I starve myself I feel different emotionally, and that’s better than feeling out of control emotionally or anxious. Likewise with bulimia, binging and purging, people numb themselves out, people also will feel high when they are binging and purging. This becomes the overwhelming only way they deal with emotions and it does work, it works at a very high price and so one of the aspects of treatment is recognizing that when you stop your eating disorder behavior you’re going to feel more anxious, you’re going to feel more out of control, emotionally. Emotionally, you’re actually going to feel worse.

The treatment then, is helping people to recognize that these emotions aren’t bad. That they can handle feeling angry, feeling upset, feeling nervous, feeling apprehensive, feeling good. And also developing different ways for dealing with those things. If someone does something to me that makes me angry, how is going to binge and throw up going to help that? Maybe going and talking with them directly. And this is something that is really a big part in relationships, when people are having issues around self-confidence or self-esteem, they have a hard time dealing with their partners if something is upsetting them. So, what you’ll typically see with someone with an eating disorder, is that they have a hard time dealing with conflict that may happen in a relationship and the eating disorder kind of becomes the way of stuffing those emotions, and it’s one of the reasons why relationships really kind of don’t work with people with eating disorders, because they’re not really working on the relationship when issues come up, when conflict arises, when something needs to be resolved.

Say more about feelings and the act of suppressing feelings.

The role that suppressing feelings plays in an eating disorder is, in my opinion, one of the critical, critical areas of recovery. You have to ask yourself, why would someone starve themselves to the point of not being able to function. Anorexia has a mortality rate of 5-10%. There’s no reason to think that males are somehow immune from that. It’s a very powerful behavior that people are engaged in. likewise with bulimia, why would someone purge to the point of ruining their teeth, really destroying their body. It’s really a powerful modulator of feelings. That is one of the things that becomes so reinforcing about it. For example, a typical history for someone with bulimia, is they start out dieting. Someone may say, I’m going to lose weight, start dieting, not be successful with that, and eat less, become hungry, then overeat, and then kind of panic. At this point most people in society know about bulimia and a certain percentage will engage in that. So for a period of time they’ll have it under control. They’ll say, gee, if I eat too much and get rid of it, I can stay with my plan of losing weight. What happens is, at some point there’s a shift, and they go, well, this isn’t a weight issue, it becomes a way of dealing with stress, of dealing with negative emotions and that’s really what the eating disorders really pick up. And that’s probably why a certain percentage of people are going to engage in similar behavior and not develop bulimia. I think that people that are at risk are the people who figure out that this helps me feel different emotionally, and those are the people who go on to develop bulimia. Certainly for a lot of people developing bulimia, I think that’s the mechanism.

Relationships –talk about the confused nurturing relationship people have with food.

What happens is when people are in their eating disorder, is that food becomes their friend. Their eating disorder becomes their best friend. They’ll frequently talk about, how can I give up my best friend? This is the person that, the relationship that I know is always there. If I’m having a bad day I know my eating disorder is there if I want it, and so there’s also an essence of mourning when they give up their eating disorder. They really are giving up something that for many people has been the thing that’s always there for them. You really need to appreciate that. People in recovery need to feel that you understand that giving this thing up is not like giving up something that’s all negative. There are many positive aspects to this, so there’s a real mourning that goes along with giving up this thing that for many years has been the first thing you do in the morning, the last thing they do at night. The eating disorder is always going to answer the phone, the eating disorder is always going to go out to dinner. That is a big deal when they’re giving that up. The whole process of saying goodbye is something that shouldn’t be underappreciated.

REVIEWS

"the most interesting—and complex—documentary at this year's [Portland LGBT Film] festival"

—Willamette Week, Portland's News Weekly

"A compelling introduction to the struggles many gay men face in their relationship with food."

—Marc Breindel, Gay.com *

“Do I Look Fat addresses body image issues in the gay community in a stirring and poignant way. The film addresses the issues directly from those affected, which makes it more meaningful. The health issues interlaced with personal messages have impact and power. This is a compelling film, one of the best made about eating disorders and a powerful piece of media for the gay community."

—Penny D. Winkle, LISW, LPCC

Eating Disorder Specialist

The Ohio State University

"Achieves the filmmaker’s intent—to promote awareness and healing."

—Mitch Rustad, GayHealth.com *

"... will help individuals and their families more accurately conceptualize the root causes of eating disorder symptoms. The men who tell their stories in this captivating film poignantly captures how gay men may still struggle with self-acceptance, and how far health care providers have yet to go in understanding and treating these illnesses."

—Daniel Garza MD *

"I could relate to everything each man said and described about themselves, not only as a gay man who has had eating disordered issues, but as a psychotherapist working with gay men with these same problems. My feeling is that this documentary should be seen by gay men and women and physicians to promote awareness and healing. More doctors than I care to mention told me that I couldn't possibly have an eating disorder because I wasn't a woman. That says it all."

—Brian Wolfe, MFT

"Timely topic. Very much needed to inform therapists to look and listen and question men's relationships to their bodies and food and not be afraid to go there less they end up colluding with issues of secrecy and shame."

"Groundbreaking! I predict this work will be the start of seminal work for males who have eating disorders."

"This was an excellent presentation and a wonderful topic sorely in need of greater coverage."

"Travis' material, skill, passion and technical accomplishment are extremely impressive. His work needs to be seen by many more people."

"Amazing! Wonderful insight inta an area that I didn't know much about. "

"Fantastic film! I can't wait to take the information back to my community."

"Excellent, I hope it's the start of more conference programming like this."

"Wonderful to see the inclusion of LGBT eating disorders at the conference."

—Clinical participants

The 15th Annual Renfrew Center Foundation Eating Disorder Conference

"At the core of this documentary is the complex issue of body image as it affects gay and bisexual men. . . Travis illustrates this unique film with compelling personal stories about a subject that has long been overlooked yet remains at the core of who we are as men and how we find acceptance. I hope this compelling work will inspire us to look at who we are and how we measure our value in the community and the world."

—Marcel Miranda, Gay/Bi Men's Program, Glide Health Services

"As bisexual and gay men we are put in a situation at an early age where we must learn to accept ourselves when society sends us much different contradictory messages. This documentary highlights the impact of such developmental confusion by telling the stories of bisexual and gay males. Their stories truly illustrate that the pressures related to sexual orientation are so strong that many frequently resort to unhealthy coping strategies. I highly recommend this documentary to anyone who is bisexual or gay, or whom knows anyone who is. This film leads the way in jump-starting an important discussion about internal-acceptance and common dysfunctional views on eating and body image."

—Shaun Adrian Flatt, Human Development Student \ GLBT Researcher

"We see that the issues for gay men are not that different from those women have been struggling with for many years, i.e. trying to find meaningful relationships in a society which emphasizes outer appearance over inner substance. Desperately craving love and acceptance, these men spend their lives trying to beautify their bodies in search of something they will never get from the superficial encounters these efforts will generate. We hear about their traumatic past, their difficulty being different in a world that encourages sameness, and their own internalized homophobia. We see them using food as a substitute for the nurturance they never got as children growing up in a homophobic society. But finally we see ourselves in the very difficult struggles involved in being a human being in the 21st century.

I highly recommend this documentary for mental health professionals and therapists, as well as for the lay public and anyone who wants to better understand their sons and daughters as well as themselves."

—Judye Hess, PhD, Family Therapist

"A controversial and intimate look at gay male society through it's eating, drug and sex disorders. Through its deconstruction Travis Mathews lays the groundwork for healing a community who often times does not want to look at its destruction for fear of backlash from the straight community. Travis takes a brave step uncovering a darkside of the San Francisco gay community in hopes of igniting change, healing pain, and bringing these issues to light. I personally was moved deeply by this film and it left me with a sense that my gay boys were going to deal with their issues and heal. the only way to enact change is to stay alive."

—Angie Leonino, Filmmaker